As Jesus was riding in and the people were crying “Hosanna in the highest,” either knowingly or not, symbolically selecting the paschal lamb for sacrifice.

Christ Entering Jerusalem Giotto di Bondone (?-1337) Scrovegni Grotto .Sunday, April 13, 2025

Palm Sunday - Jesus Entering Jerusalem as The Messiah

The Passover story from the Old & New Testaments in the Christian Bible relates that God had sent Moses to free the Israelites from slavery in Egypt & bring them into the Promised Land. But Pharaoh refused to let them go, saying “Who is the Lord, that I should obey him & let Israel go? I do not know the Lord & I will not let Israel go” (Exodus 5:2). Pharaoh considered himself to be a god, & therefore equal to any other god.

And so, it is written in The Bible, God had brought a series of plagues against Egypt. He turned their water to blood. He caused an infestation of frogs, then one of gnats, & after that, one of flies. He made their livestock drop dead. He caused an outbreak of painful boils, a great hailstorm that destroyed their crops, a plague of locusts that ate what was left, & another of darkness. Through these 9 plagues, Pharaoh had remained just as obstinate as God had predicted, & refused to let the Israelites go.

The Lord had said to a worried Moses, “I will bring one more plague on Pharaoh & on Egypt. After that, he will let you go from here, & when he does, he will drive you out completely.” (Exodus 11:1-2). The 10th plague, the death of all the firstborn, would break Pharoah’s will & free the Israelites from their bondage, but first they had to be protected from it. On the 10th day of the 1st month God had them select a male lamb for each household & inspect it for 3 days to be sure it had no blemish or defect. Then it was slaughtered, & its blood was applied to the door posts of their homes. Sunset brought the 14th of the month, & after cooking the lamb, each family gathered behind closed doors in their own house, & ate it quickly with some bitter herbs & unleavened bread, not venturing outside. It is reported that at midnight the destroying angel came through Egypt & took the life of the first born of every family, except for those who had covered their door posts with lamb’s blood (Exodus 12:1-13, 21-23, 28-30).

Two years after the exodus from Egypt the Lord had Moses take a census of the all the people, listing by name every male 20 years old or older who could serve in the army. The number of those who met the requirements totaled 603,550 (Numbers 1:1-46). Most scholars agree that the total Israelite population would have been about 1.5 million at the time.

On the first Christian Palm Sunday, the 10th day of the 1st month, another Passover Lamb was selected by allowing people to hail Him as Israel’s King for the first & only time in His life. When the Pharisees told him to rebuke His disciples for doing so, He said if they kept silent the very stones would cry out (Luke 19:39-40).

Saturday, April 12, 2025

Palm Sunday - Jesus Entering Jerusalem as The Messiah

.jpg)

Passover was only 4 days away, when Jesus rode a donkey into Jerusalem that year. He entered the city on the 10th day of the month. Exodus 12:3, 5-6, says, Speak ye unto all the congregation of Israel, saying, In the tenth day of this month they shall take to them every man a lamb, according to the house of their fathers, a lamb for an house.. . ..Your lamb shall be without blemish, a male of the first year: ye shall take it out from the sheep, or from the goats: And ye shall keep it up until the fourteenth day of the same month: and the whole assembly of the congregation of Israel shall kill it in the evening.

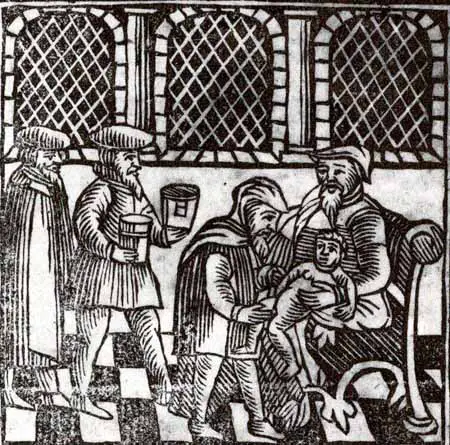

Passover - Judaism Religious Rituals depicted in 1707

The woodcuts in the book cover Sabbath & holiday observance, & home & synagogue rituals. Among them area mother blessing the Sabbath lights of a Sabbath oil lamp;a father chanting the Havdalah (service of "separation" at the conclusion of the Sabbath), while he holds a cup of wine by the light of a candle held by a child whose sibling holds a spice box; 4 men blessing the new moon;a rabbi preaching on the Great Sabbath (preceding Passover); grinding flour for & baking matzoh; searching for chametz (leaven); & scouring pots & pans. Also shown are a man having his hair cut on Lag B'Omer--the 33rd day of the 50 between Passover & Shavuot, when restrictions obtaining during that period of mourning are relaxed; Moses on Sinai receiving the Ten Commandments; worshipers seated on the floor on Tisha B'Av, mourning the destruction of the Temple; the sounding of the shofar on Rosh Hashanah, the New Year; a man building his tabernacle for the Feast of Tabernacles; the gathering of palms, willows, & myrtle to join the citron in its celebration; children receiving sweets to celebrate the Joy of the Law, Simhat Torah; the kindling of a Hanukkah lamp; & Purim jesters sounding their musical instruments.

The life cycle is also marked: bride & groom under the huppah (canopy); an infant boy entering the Covenant of Abraham; & finally, a body borne in a coffin to its eternal resting place. These are some of the 1707 woodcuts:

Passover History from the Hebrew Bible

Passover Preparations in the Sister Haggadah. British Library (Public Domain)

Unleavened bread, matzo or matzah, is a type of bread that is made without yeast or any other leavening agent. It is typically made from flour & water & is often eaten during the Jewish holiday of Passover, where it symbolizes the haste with which the Israelites left Egypt & the lack of time to let their bread rise. The Bible does not specify which grains were used for this bread, but it is likely that the bread mentioned in the Bible was made from wheat, barley, or spelt, which were common grains in the ancient Near East.

Bitter herbs are a variety of herbs that are eaten during the Passover Seder to symbolize the bitterness of slavery in Egypt. The bitter herbs are typically dipped in salt water before eating to represent the tears shed during the Israelites' slavery in Egypt.

The Bible does not specify which grains were used for this unleavened bread, but it is likely that the bread mentioned in the Bible was made from wheat, barley, or spelt, which were common grains in the ancient Near East.

Bitter herbs are oftren a combination of herbs that are eaten during the Passover Seder to symbolize the bitterness of slavery in Egypt. The bitter herbs are often dipped in salt water before eating to represent the tears shed during the Israelites' slavery in Egypt.

The Mishnah specifies 5 types of bitter herbs eaten on the night of Passover: ḥazzeret (lettuce), ʿuleshīn (endive/chicory), temakha, ḥarḥavina (possibly melilot, or Eryngium creticum), & maror (likely Sonchus oleraceus, sowthistle).

Hazzeret

Hazzeret isthought to be a domestic lettuce. The word is cognate to other Near-Eastern terms for lettuce: the Talmud identifies hazzeret as hassa, similar to the Akkadian hassu & the Arabic hash.

The Talmud remarks that Romaine lettuce is not initially bitter, but becomes so later on, which is symbolic of the experience of the Jews in Egypt. The "later" bitterness of lettuce refers to fact that lettuce plants become bitter after they "bolt" (flower), a process which occurs naturally when days lengthen or temperatures rise.

Wild or prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola) is listed in Tosefta Pisha as suitable for maror. However, its absence from the approved list in the Mishnah & Talmud indicate that it is not suitable.

`Ulshin

The second species listed in the Mishnah is `ulshin, which is a plural to refer to both wild & cultivated types of plants in the genus Cichorium. The term is cognate to other near-eastern terms for endives.

Tamcha

The Talmud Yershalmi identified Hebrew tamcha with Greek γιγγίδιον gingídion, which has been positively identified via the illustration in the Vienna Dioscurides as the wild carrot Daucus gingidium.

Horseradish likely began to be used later, because leafy vegetables like lettuce did not grow in the northern climates Ashkenazi Jews had migrated to, & because some sources allow the use of any bitter substance.

Many Jews use horseradish condiment (a mixture of cooked horseradish, beetroot & sugar), though the Shulchan Aruch requires that maror be used as is, that is raw, & not cooked or mixed with salt, vinegar, sugar, lemon, or beets.

Harhavina

The identity of harhavina is somewhat disputed. It may be melilot or Eryngium creticum.

Maror

The identity of this species was preserved among the Jews of Yemen as the plant Sonchus oleraceus, a relative of dandelion native to Israel. The word "maror" is an autohyponym, referring both to this species specifically, & to any species suitable for use at the Seder.

Passover in the Hebrew Bible by William Brown

Passover is a Jewish festival celebrated since at least the 5C BCE, typically associated with the tradition of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt. The festival was originally celebrated on the 14th of Nissan. Directly after Passover is the Festival of Unleavened Bread, which most traditions describe as originating when the Israelites left Egypt, & they did not have sufficient time to add yeast to the bread to allow it to rise.

Though the Hebrew Bible describes the origins of Passover, these texts were likely composed after the 6C BCE & include evidence for editorial additions, expansions of older texts. Three characteristics emerge concerning the nature of Passover as represented in the Hebrew Bible:

Passover is associated with Yahweh, though not necessarily Yahweh's leading the Israelites out of Egypt or passing over the doorposts of their households. In analyzing & proposing a history for the textual growth of Exodus 12:1-28, Professors Simeon Chavel & Mira Balberg suggest that the oldest layer of text in Exodus 12 does not feature "Israel's liberation through Yahweh's smiting of Egypt & does not explicitly advance it" (Chavel 2018, 299), essentially characterizing it as an ambiguous piece of folklore about a festival.

Subsequent editors provided further ritual parameters & explanation of Yahweh's actions: all Israelite families must participate in consuming a one-year-old male lamb; the lamb should be flame-broiled, entirely consumed by the morning after Passover, & eaten quickly; & Yahweh will skip over or shield the Israelite households who put the lamb's blood on the doorpost from a destructive force killing their firstborn. Exodus 12:27, a response to the question concerning the purpose of celebrating Passover in future generations, best demonstrates the association between Passover & the killing of every firstborn in Egypt: “It is a Passover sacrifice for Yahweh, who passed over the houses of the Israelites in Egypt when smiting Egypt; but he rescued our homes.” Passover was intended to be a performance & remembrance of Yahweh's act of protecting the firstborns of Israel while in Egypt, itself a sign of Yahweh's devotion to the Israelites.

Though Passover is often perceived as a unified, traditional ritual, Biblical passages describe divergent rituals & reflect changes over time in the historical context.

The rituals concerning the actions on Passover develop throughout the Hebrew Bible such as this example, in Exodus 12:9. Moses commands the Israelites to roast with fire the Passover lamb sacrifice, explicitly indicating they should not boil it with water. Yet, Deuteronomy 6:7 includes the command “you shall boil” the Passover sacrifice. Then, the author of Chronicles creatively combined the required ritual actions: “So, they boiled the Passover-lamb with fire according to the ordinance” (35:13). Subsequent generations adjusted Passover ritual traditions.

Third, texts in the Hebrew Bible adjust the date of Passover for distinct reasons. Numbers 9:1-14, for example, offers provisions for Israelites who may have missed their opportunity to participate in Passover due to ritual uncleanliness (9:7, 10). Alternatively, Yahweh communicates through Moses that a 2nd Passover celebration is possible. Instead of celebrating on the 14th day of the 1st month, they should celebrate on the 14th day of the 2nd month. There remains an assumption, though, that all Israelites should celebrate Passover: "But the man who is pure, not on a journey, & neglects to perform the Passover, that person should be cut off from his people because he did not bring the offering of Yahweh at its appointed time." (Numbers 9:13).

The book of 2 Chronicles 30 describes Hezekiah's attempt to cause all of Judah & Israel to perform Passover. The text describes that they celebrated it on the 14th of the second month due to the lack of priests available & people present (2 Chronicles 30:2-3). Numbers 9 understands Passover to be an obligation incumbent on the Israelites; when 2 Chronicles 30 was composed, Passover was not perceived to be an obligation upon Israel & Judah.

Exodus 12 presents Passover as a celebration restricted to the households of Egypt (Exodus 12:1-13). Deuteronomy 16 indicates that Passover should be celebrated not at the home: “and you shall sacrifice a Passover-offering to Yahweh, either a sheep or a cattle, at the place which Yahweh will select as a dwelling for his name” (Deuteronomy 16:2), specifically clarifying in Deuteronomy 16:5 that the sacrifice should not be offered locally. When Exodus 12 was composed, Passover was practiced in local towns & households; by contrast, when Deuteronomy 16 was composed, Passover was more regulated, imagined to be practiced in a central temple or sanctuary.

Biblical passages describe divergent rituals, reflect the growth of the Passover tradition, & illuminate changes in the historical context.

Practicing Passover across the Centuries

Early Judaism (c. 5C BCE - 1st C CE) In a group of texts called the Elephantine Papyri, written by members of the 5C BCE Jewish colony of Elephantine, Egypt, Passover is mentioned multiple times. indicating that Jews at Elephantine practiced some form of Passover. Unlike the biblical texts, the Elephantine Papyri can be more precisely dated affirming that Passover was a social practice among some Jews in the 5C BCE.

Composed in the 2C BCE, the Book of Jubilees is a rewritten version of Genesis & Exodus. One goal of Jubilees is to clarify the Jewish calendar for celebrating festivals. The book of Genesis narrates a story about how Yahweh tested Abraham by commanding him to kill his only son, providing a ram at the last minute. Jubilees 19:18, though, additionally describes how Abraham celebrated a festival for Yahweh after Yahweh provided a ram in lieu of having to sacrifice Isaac, his firstborn. The festival is the Festival of Unleavened Bread, which is typically associated with Passover, occurring 7 days following Passover. Jubilees establishes that the Festival of Unleavened Bread, thar Passover, was established prior to the Israelite exodus out of Egypt.

Passover in Early Christianity (c. 1C CE to 3C CE)

Passover plays a central role in the growth of Christianity as a distinct religious tradition from Judaism. By the 1C CE, Josephus & the Gospels indicate that Passover drew large crowds of Jews to Jerusalem, the central cult site for the celebration of Passover. Jesus he was a practicing Jew who lived in the 1C CE.

Jesus & The Last Supper

John 19:31 portrays Jesus as a Passover lamb, whose sacrifice would ultimately cause God to redeem humanity. Paul explicitly describes Jesus as a Passover lamb as he extends the imagery of unleavened bread metaphorically into the realm of morality (1 Corinthians 5:6-8). Similar depictions of Jesus appear in 1 Peter 1:19 & Revelation 5:6. The association of Jesus' death with the Passover sacrifice “points to an understanding of the sacrifices of the Passover lamb as the remembrance of God's past act of redemption that foreshadowed the sacrifice of the Lamb of God as God's ultimate act of redemption” (Mangum 2016). Early Christians, who perceived themselves as practicing Jews, reframed the traditional narrative of Passover to highlight Jesus as a redemptive figure for all of humanity.

Rabbinic Judaism (c 1C CE to 7C CE)

Rabbinic Judaism developed, in response to the destruction of the Jewish temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. Without the temple, Jews could no longer offer sacrifices. It is from this context which Rabbinic Judaism emerged, providing ways to worship God & perform the various ritual festivals even though the Jewish temple was no longer standing. Rabbinic Judaism sought to establish “that the Passover celebration can & should continue even without the paschal lamb,” that is the Passover lamb (Bokser 1984, 48). Although ancient Israelite & Judean religion, along with Early Judaism, perceived the temple to be central to their worship, the destruction of the Jewish temple in 70 CE forced the Rabbis to reconsider how they would perform their ancient rituals.

The Tosefta, a Rabbinic Jewish text of codified traditions & laws (3C CE), discusses the role of unleavened bread & bitter herbs, two foods mentioned in Exodus 12:8: “They shall eat the flesh that same night; they shall eat it roasted over the fire, with unleavened bread & with bitter herbs” (Exodus 12:8; 1985 JPS Translation). Because this passage indicates that 3 things are eaten together, namely the Passover lamb, bitter herbs, & unleavened bread, the Rabbis equated bitter herbs & unleavened bread with the Passover sacrifice.

Passover in the Ancient Near East

Passover as a festival is reflective of its broader ancient Near Eastern context in the use of blood at the entrance of the house combined with regard to the firstborn. One of the fundamental aspects of Passover is putting the blood of the Passover lamb upon the gateposts of the household, that is the front entrance: They shall take from the blood of the Passover lamb & put it upon the two doorposts & upon the upper-cross piece of the door upon the house within which they will eat it among them. (Exodus 12:7)

Applying the blood onto the door of the household warded off negative influences. In the context of Exodus 12, the “negative influence” is reference yo the destructive force which kills every firstborn.

Likewise, the Arslan Tash amulet from the 7C BCE discovered in Syria, includes a reference to “doorposts:” “And let him not come down to the door-posts.” Here, the “doorposts” are the boundary into the home, the location where the amulet was possibly placed for preventing negative influences on the household.

Additionally, a ritual called zukru, from a text discovered in Emar, Syria, shows remarkable similarities to Passover. First, both festivals began on the 14th day of the 1st month, lasting 7 days. Second, the ritual for Passover & zukru both involve the smearing of blood on posts – the posts in Passover are to the house, the posts in zukru are at the city gates. Third, zukru is primarily a festival of “(the offering of) the (firstborn) male animals” to Dagan, a Syrian deity (Cohen 2015, 336). Likewise, Exodus 34:19 associates Passover with the offering of firstborn animals. The speaker, Yahweh, says: “All first-born of a womb are mine, as well as your male livestock, the first born of cattle & sheep.” These passages demonstrate that Passover rituals are similar to broader ancient Near Eastern traditions.

Tuesday, December 24, 2024

Monday, October 28, 2024

How did Halloween Begin?

How Did Halloween Begin?

Samhain, an Ancient Celtic festival

Halloween’s origins can be traced back to antiquity. Most point to Samhain, a Celtic festival which commemorated the end of the harvest season & the blurring of the physical & spirit worlds, as Halloween’s origin. Over the ages, the ancient, pagan Celtic holiday evolved, taking on Christian influences, European myths, & American consumerism.

Samhain was one of the most important & sinister calendar festivals of the year. At Samhain, held on November 1, the world of the gods was believed to be made visible to humankind, & the gods played many tricks on their mortal worshippers; it was a time fraught with danger, charged with fear, & full of supernatural episodes.

Sacrifices & propitiations of every kind were thought to be vital, for without them the Celts believed they could not prevail over the perils of the season or counteract the activities of the deities. Samhain was an important precursor to Halloween.

Ancient Celts marked Samhain as the most significant of the 4 quarterly fire festivals, taking place at the midpoint between the fall equinox & the winter solstice. During this time of year, hearth fires in family homes were left to burn out while the harvest was gathered.

After the harvest work was complete, celebrants joined with Druid priests to light a community fire using a wheel that would cause friction & spark flames. The wheel was considered a representation of the sun & used along with prayers. Cattle were sacrificed, & participants took a flame from the communal bonfire back to their home to relight the hearth.

Early texts present Samhain as a mandatory celebration lasting 3 days & 3 nights where the community was required to show themselves to local kings or chieftains .the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, when people would light bonfires and wear costumes to ward off ghosts. Failure to participate was believed to result in punishment from the gods, usually illness or death.

There was also a military aspect to Samhain in Ireland, with holiday thrones prepared for commanders of soldiers. Anyone who committed a crime or used their weapons during the celebration faced a death sentence.

Some documents on Samhain, the Celtic festival mention 6 days of drinking alcohol to excess, typically mead or beer, along with gluttonous feasts.

By A.D. 43, the Roman Empire had conquered the majority of Celtic territory. In the course of the 400 years that they ruled the Celtic lands, two festivals of Roman origin were combined with the traditional Celtic celebration of Samhain.

The first was Feralia, a day in late October when the Romans traditionally commemorated the passing of the dead. The second was a day to honor Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit and trees. The symbol of Pomona is the apple, and the incorporation of this celebration into Samhain might explain the tradition of bobbing for apples that is still practiced on Halloween.

On May 13, A.D. 609, the Christian Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Pantheon in Rome in honor of all Christian martyrs, & the Catholic feast of All Martyrs Day was established in the Western church. Pope Gregory III later expanded the festival to include all saints as well as all martyrs, & moved the observance from May 13 to November 1.

By the 9th century, the influence of Christianity had spread into Celtic lands, where it gradually blended with & supplanted older Celtic rites. In A.D. 1000, the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to honor the dead. It’s widely believed today that the church was attempting to replace the Celtic festival of the dead with a related, church-sanctioned holiday.

All Souls’ Day was celebrated similarly to Samhain, with big bonfires, parades & dressing up in costumes as saints, angels & devils. The All Saints’ Day celebration was also called All-hallows or All-hallowmas (from Middle English Alholowmesse meaning All Saints’ Day) & the night before it, the traditional night of Samhain in the Celtic religion, began to be called All-Hallows Eve &, eventually, Halloween.

All Saints' Day

On May 13, A.D. 609, Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Pantheon in Rome in honor of all Christian martyrs, and the Catholic feast of All Martyrs Day was established in the Western church. Pope Gregory III later expanded the festival to include all saints as well as all martyrs, and moved the observance from May 13 to November 1.

By the 9th century, the influence of Christianity had spread into Celtic lands, where it gradually blended with and supplanted older Celtic rites. In A.D. 1000, the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to honor the dead. It’s widely believed today that the church was attempting to replace the Celtic festival of the dead with a related, church-sanctioned holiday.

All Souls’ Day was celebrated similarly to Samhain, with big bonfires, parades and dressing up in costumes as saints, angels and devils. The All Saints’ Day celebration was also called All-hallows or All-hallowmas (from Middle English Alholowmesse meaning All Saints’ Day) and the night before it, the traditional night of Samhain in the Celtic religion, began to be called All-Hallows Eve and, eventually, Halloween.

See: History.org, Halloween 2023, August 11, 2023

Library of Congress Blog, The Origins of Halloween Traditions, October 26, 2021, by Heather Thomas

Sunday, October 27, 2024

Halloween's Celtic & Christian Origins over 2,000 years ago.

A traditional Irish Halloween carved turnip jack-o-lantern

The traditions of "guising," & "mumming" grew into an event where masked individuals would go door-to-door disguised as spirits dancing & singing in exchange for food & wine.

Friday, October 11, 2024

Thursday, October 10, 2024

Wednesday, October 9, 2024

Tuesday, October 8, 2024

Monday, October 7, 2024

Sunday, October 6, 2024

Saturday, October 5, 2024

Friday, October 4, 2024

Women & Gardens - Europe

+Marie+in+the+Garden.jpg)

Thursday, October 3, 2024

Wednesday, October 2, 2024

Tuesday, October 1, 2024

Euro Gardens Women & Gardens - Europe

Mary E Harding. (English artist, 1880-1903)

Norman Prescott Davies (British artist, 1862-1915), Iris

Harold Harvey (British artist, 1874–1941) Picking Flowers

Edward Killingworth Johnson (British artist, 1825 - 1923) Lady picking flowers

Emile Baes (Belgian artist, 1879-1953) In the Garden

Emma Ekwall (Swedish artist, 1838-1930)

Hermann Seeger (German artist, 1857-1945) Picking Wild Flowers 1905

Alfred Émile Stevens (Belgian painter, 1823-1906) Afternoon in the Park

Claude Monet (French artist, 1840-1926) Girl in the Garden at Giverny

Alfred Émile Stevens (Belgian painter, 1823-1906) Reverie

Laura Muntz Lyall (Canadian painter, 1860-1930) Oriental Poppies

Archibald George Barnes (British artist, 1887-1972) The Parasol

Jean Édouard Vuillard (1868-1940) Morning Graden

+Entry+into+Jerusalem.jpg)

%20The%20Last%20Supper%202.jpg)

++Morning+Graden.jpg)

+Woman+Beside+a+Chestnut+Tree.jpg)

.In+the+Pergola+1892.jpg)

++Alice+Hoschede+in+the+Garden.jpg)

+Woman+Reading+in+a+Garden.jpg)

+Dziewczynka+z+koszem+jarzyn+w+ogrodzie+1891.jpg)

+Young+Woman+in+a+Rosegarden+1899.jpg)

+In+the+Garden+1870.jpg)

++Peonies+1889.jpg)

+Dutch+woman+in+a+garden.jpg)

.jpg)

,+Iris.jpg)

+Picking+Flowers.jpeg)

+Lady+picking+flowers.jpg)

++In+the+Garden.jpg)

+Picking+Wild+Flowers+1905.jpg)

+Afternoon+in+the+Park+afternoon_in_the_park-large.jpg)

+Reverie.jpg)

+Oriental+Poppies.jpg)

+The+Parasol.jpg)