Christmas celebrations in New England were illegal during parts of the 17C. The Puritan community found no scriptural justification for celebrating Christmas, & associated such celebrations with paganism & idolatry.

The earliest years of the Plymouth Colony were troubled with non-Puritans attempting to make merry, & Governor William Bradford was forced to reprimand offenders.

English laws suppressing the holiday were enacted in the English Interregnum, but repealed late in the 17C. However, the Puritan view of Christmas & its celebration had gained cultural ascendancy in New England, & Christmas celebrations continued to be discouraged despite being legal.

But by the mid-18C, Christmas had become a mainstream celebration in New England, & by the beginning of the 19C, ministers of Congregational churches, the church of the Puritans, actually called for formal observance of Christmas in the churches.

When Christmas became a federal holiday in 1870, late 19C Americans widely fashioned the day into the Christmas of commercialism, spirituality, & nostalgia that most Americans recognize today.

In Puritans at Play (1995), Bruce Colin Daniels writes "Christmas occupied a special place in the ideological religious warfare of Reformation Europe." Most Anabaptists, Quakers, & Congregational & Presbyterian Puritans, he observes, regarded the day as an abomination while Anglicans, Lutherans, the Dutch Reformed, & other denominations celebrated the day as did Roman Catholics. When the Church of England promoted the Feast of the Nativity as a major religious holiday, the Puritans attacked it as "residual Papist idolatry."

Cotton Mather, c. 1700

Puritans heaped contempt on Christmas, Daniels writes, calling it 'Foolstide' & suppressing any attempts to celebrate it for several reasons. First, no holy days except the Sabbath were sanctioned in Scripture, second, the most egregious behaviors were exercised in its celebration (Cotton Mather railed against these behaviors), & third, December 25 was ahistorical.

The Puritan argued that the selection of the date was an early Christian hijacking of a Roman festival, & to celebrate a December Christmas was to defile oneself by paying homage to a pagan custom. James Howard Barnett notes in The American Christmas (1984) that the Puritan view prevailed in New England for almost 2 centuries.

The Examination & Tryal of Father Christmas (1686)

The Plymouth Pilgrims put their loathing for the day into practice in 1620, when they spent their first Christmas Day in the New World building their first structure in the New World to demonstrate their complete contempt for the day.

Governor William Bradford (1590-1657)

A year later on December 25, 1621, Governor William Bradford led a work detail into the forest & discovered some recent arrivals among the crew had scruples about working on the day.

On the day called Christmas Day, the Governor called the settlers out to work as was usual. However, the most of this new company excused themselves & said it went against their consciences to work on that day. So the Governor told them that if they made it a matter of conscience, he would spare them till they were better informed; so he led away the rest & left them.

When the Governor & his crew returned home at noon they discovered those left behind playing stool-ball, pitching the bar, & pursuing other sports. Bradford confiscated their implements, reprimanded them, forbade any further reveling in the streets, & told them their devotion for the day should be confined to their homes.

Later that day, however, when they were found playing in the streets, which supposedly went against their strict religious beliefs, they were told that “if they made the keeping of it (Christmas) matter of devotion, let them keep their houses; but there should be no gaming or reveling in the streets,” according to William Bradford. The Pilgrims' 2nd governor, William Bradford (1590-1657,) wrote that he tried hard to stamp out "pagan mockery" of the observance, penalizing any frivolity.

On Christmas Day, 1620, Governor Bradford encountered a group of people who were taking the day off from work & wrote in his journal: "And herewith I shall end this year. Only I shall remember one passage more, rather of mirth then of waight. One ye day called Christmas-day, ye Govr caled them out to worke, (as was used,) but ye most of this new-company excused them selves & said it wente against their consciences to work on yt day. So ye Govr tould them that if they made it mater of conscience, he would spare them till they were better informed. So he led-away ye rest & left them; but when they came home at noone from their worke, he found them in ye streete at play, openly; somepitching ye barr, & some at stoole-ball, & shuch like sports. So he went to them, & tooke away their implements, & tould them that was against his conscience, that they should play & others worke. If they made ye keeping of it mater of devotion, let them kepe their houses, but ther should be no gameing or revelling in ye streets. Since which time nothing hath been atempted that way, at least openly."

Massachusetts & Connecticut followed the Plymouth Colony in refusing to condone any observance of the day. When the Puritans came to power in England following the execution of King Charles I of England, Parliament of England enacted a law in 1647 abolishing the observance of Christmas, Easter, & Whitsuntide. The Puritans of New England then passed a series of laws making any observance of Christmas illegal, thus banning Christmas celebrations for part of the 17C. A Massachusetts law of 1659 punished offenders with a hefty 5 shilling fine.

Sir Edmund Andros

Laws suppressing the celebration of Christmas were repealed in 1681, but staunch Puritans continued to regard the day as an abomination. Eighteenth century New Englanders viewed Christmas as the representation of royal officialdom, external interference in local affairs, dissolute behavior, & an impediment to their holy mission.

During Anglican Governor Sir Edmund Andros tenure (December 20, 1686 – April 18, 1689), for example, the royal government closed Boston shops on Christmas Day & drove the schoolmaster out of town for a forced holiday. Following Andros' overthrow, however, the Puritan view reasserted itself & shops remained open for business as usual on Christmas with goods such as hay & wood being brought into Boston as on any other work day.

With such an onus placed upon Christmas, non-Puritans in colonial New England made no attempt to celebrate the day. Many spent the day quietly at home. In 1771, Anna Winslow, an American schoolgirl visiting Boston noted in her diary, "I kept Christmas at home this year, & did a good day's work."

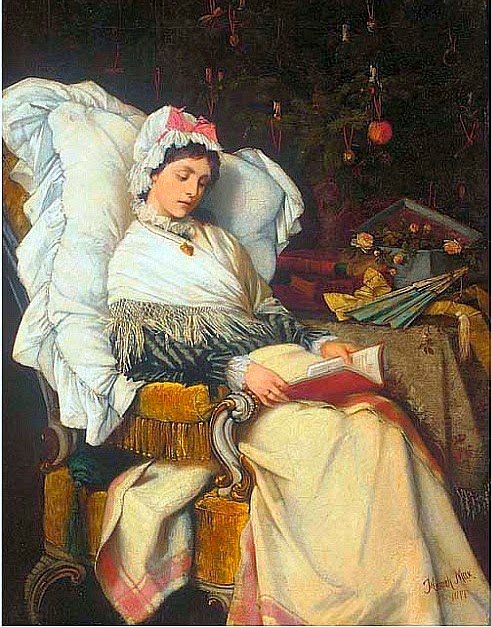

Although Christmas celebrations were legal after 1680, New England officials continued to frown upon gift giving & reveling. Evergreen decoration, associated with pagan custom, was expressly forbidden in Puritan meeting houses & discouraged in the New England home. Merrymakers were prosecuted for disturbing the peace.

Christmas began to become respectable in the 18C. Even Cotton Mather's 1712 anti-Christmas sermon did argue against inappropriate behavior during Christmas, but he allowed for the possibility of celebrating it. By 1730s, there were sermons positively urging that Christmas was a joyful occasion. A few almanacs started mentioning Christmas in 1713, but by the 1760s, it became common. Christmas poems were printed in New England newspapers on multiple occasions, both for adults & for children. Christmas music was printed starting in the 1760s.

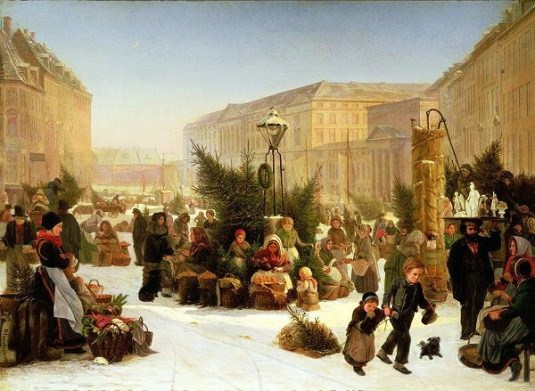

The 1st public call by a Congregationalist for a church celebration of Christmas came in 1797. The Universalists started holding Christmas services in 1789, & the Unitarians started advocating for closing businesses on Christmas in 1817. From 1818 to the late 1820s, there was a short-lived movement to hold Christmas services in churches, & to close businesses. Yet the commercial side of Christmas was already beginning to take hold: by 1808, there were already advertisements for Christmas gifts, & the modern version of Christmas was being created.

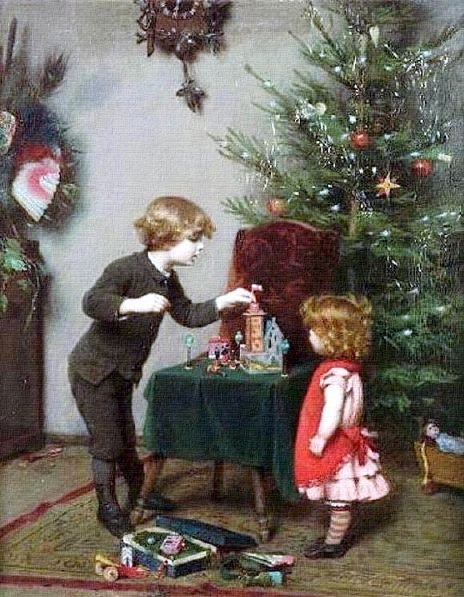

In New England, as elsewhere, the next incarnation of Christmas was taking shape. That incarnation engaged powerful new forces that were coming to dominate much of American society in the years after 1820—a heady brew that mixed a rapidly commercializing economy with a culture of domesticity centered on the well-being of children. Both elements were present in a new Christmas poem that soon came to define the rituals of the season in middle-class households throughout the United States. This new poem, written in 1822, began to receive wide distribution in the newspaper press (including that of New England) 5 years later. Although it was set on the night before Christmas, its subject was not the nativity but 'A Visit from St. Nicholas.'

So it would be Santa Claus, not Jesus of Nazareth, whose influence finally succeeded in transforming Christmas from a season of misrule into a day of quieter family pleasures. In 1856, Christmas became a public holiday in Massachusetts.

As late as 1870, classes were scheduled in Boston public schools on Christmas Day & punishments were doled out to children who chose to stay home beneath the Christmas tree. One commentator hinted that the Puritans viewed Santa Claus as the Anti-Christ.

In the aftermath of the American Civil War, Christmas became the festival highpoint of the American calendar. The day became a Federal holiday in 1870 under President Ulysses S. Grant in an attempt to unite north & south. During the 19C the Puritan hostility to Christmas gradually relaxed.

In the late 19C, authors praised the holiday for its liberality, family togetherness, & joyful observance. In 1887, for example, St. Nicholas Magazine published a story about a sickly Puritan boy of 1635 being restored to health when his mother brings him a bough of Christmas greenery.

When the day's less pleasant associations were stripped away, Americans recreated the day according to their tastes & times. The doctrines that caused the Puritans to regard the day with disapprobation were modified & the day was rescued from its traditional excesses of behavior. Christmas was reshaped in late 19C America with liberal Protestantism & spirituality, commercialism, artisanship, nostalgia, & hope becoming the day's distinguishing characteristics. See Wikipedia

.+Feast+of+St+Nicholas+1665.jpg)

+A+traveling+family+of+beggars+is+rewarded+by+poor+peasants+on+Christmas+Eve+1834.jpg)

,+Christmas+Eve.jpg)

+Christmas+Morning+1800s.jpg)

+Hanging+the+Mistletoe+1892.jpg)

+The+Christmas+Tree+1911.jpg)

+Katya+in+Blue+Dress+by+Christmas+Tree+1922.jpg)

++The+Christmas+Hamper+1874.jpg)

,+Christmas+Morning+1844.jpg)

+Children+Anticipating+the+Christmas+Feast+1840.jpg)

+A+Christmas+Dole+1800s.jpg)

,+Under+the+Mistletoe+1865.jpg)

+Distributing+Christmas+Presants+1913.jpg)

+Christmas+1939.jpg)

+Christmas+Morning+Service+1908.jpg)

++Santa+with+Toys+1910-20.jpg)

+Christmas+Spirit+1921.jpg)

+Christmas+1903-04.jpg)

+Christmas+1910.jpg)

+Christmas+Eve+1927.jpg)