Sinter Klaas Comes to New York

The name Santa Claus evolved from Nick's Dutch nickname, Sinter Klaas, a shortened form of Sint Nikolaas (Dutch for Saint Nicholas). St. Nicholas made his first inroads into American popular culture towards the end of the 18th century. In December 1773, and again in 1774, a New York newspaper reported that groups of Dutch families had gathered to honor the anniversary of his death.

The British demanded taxes from the American colonies but refused to give them a representative in Parliament. Following the incident known as the "Boston Tea Party," patriots started to organize societies to obstruct the British imperialists. In New York, they called themselves "Sons of Saint Nicholas", as an alternative to the pro-British societies of Saint George. In this way, Nicholas became a symbol of New York's non-English past, and he was therefore accepted as patron of the newly founded New York Historical Society.

In 1809, Washington Irving (1783-1859), helped to popularize the Sinter Klaas stories when he referred to St. Nicholas as the patron saint of New York in his book, The History of New York. As his prominence grew, Sinter Klaas was described as everything from a "rascal" with a blue three-cornered hat, red waistcoat, and yellow stockings to a man wearing a broad-brimmed hat and a "huge pair of Flemish trunk hose." In fact, Irving invented a tradition. His Nicholas resembled a corpulent Dutch citizen, smoking a Goudse pijp (a long white pipe made of clay, produced in Gouda). The venerable bishop had become "a chubby and plump, right jolly old elf", as he is called in the anonymous poem called A Visit From Saint Nicholas (1823). Within 15 years, Father Christmas, including his fur-trimmed red dress, reindeers, sleigh, and cherry nose had been invented.Put on the Tabard, best you can,Go, clad therewith, to Amsterdam,From Amsterdam to Hispanje,Where apples bright of Oranje,And likewise those granate surnam’d.Saint Nicholas, my dear good friend!To serve you ever was my end,If you will, now, me something give,I’ll serve you ever while I live.

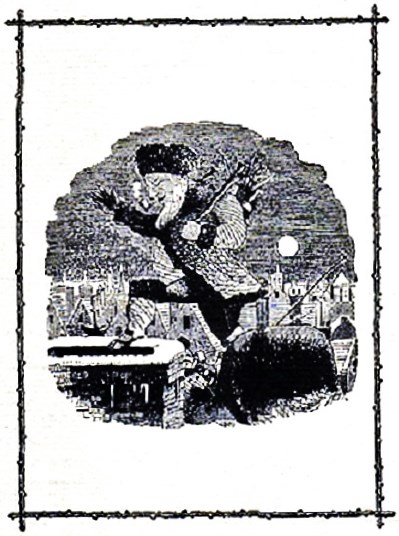

One the earliest illustrations (artist unknown) of Santa Claus, the secular character having evolved from St. Nicholas. This picture shows him on a rooftop with his sleigh & a reindeer for the first time.

In 1821, a small, 16-page booklet appeared, titled A New Year’s Present for the Little Ones from Five to Twelve, Part III. It was about Christmas, and was the first to picture Santa Claus in a sleigh drawn by a reindeer. Published by William B. Gilley of New York, no credit was given to either the author or the illustrator. Part of the verse is reproduced below:

Old Santeclaus with much delightHis reindeer drives this frosty night,O’er chimney tops, and tracks of snow,To bring his yearly gifts to you.The steady friend of virtuous youth,The friend of duty, and of truth,Each Christmas eve he joys to comeWhere love and peace have made their home.Through many houses he has been,And various beds and stockings seen;Some, white as snow, and neatly mended,Others, that seem’d for pigs intended.Where e’er I found good girls or boys,That hated quarrels, strife and noise,I left an apple, or a tart,Or wooden gun, or painted cart;To some I have a pretty doll,To some a peg-top, or a ball;No crackers, cannons, squibs, or rockets,To blow their eyes up, or their pockets.No drums to stun their Mother’s ear,Nor swords to make their sisters fear;But pretty books to store their mindWith knowledge of each various kind.But where I found the children naughty,In manners rude, in temper haughty,Thankless to parents, liars, swearers,Boxers, or cheats, or base tale-bearers,I left a long, black, birchen rod.Such as the dread command of GodDirects a Parent’s hand to useWhen virtue’s path his sons refuse.