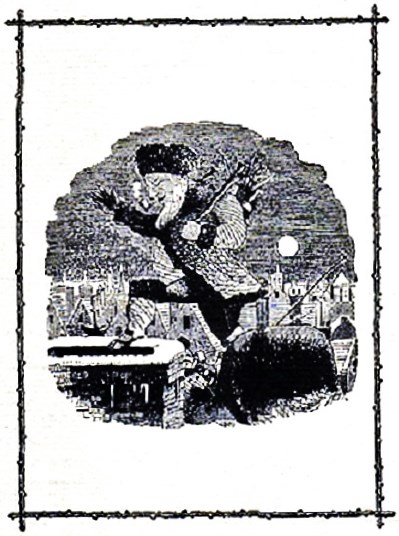

1861 'Wassailing apple-trees with hot cider in Devonshire on twelfth eve'

It is difficult to tell when "wassailing" orchards in the Christmas season first began, wishing the trees health and abundant crops in the coming year. Soon hopeful farmers wassailed both crops and animals to encourage fertility. An observer recorded, "They go into the Ox-house to the oxen with the Wassell-bowle and drink to their health."

In the 18C, farmers in the west of Britain toasted the good health of apple trees to promote an abundant crop the next year. Some placed cider-soaked bread in the branches to ward off evil spirits. Others splashed the trees with cider while firing guns or beating pots and pans. Sometimes they sang special songs:

Let every man take off his hat

And shout out to th'old apple tree

Old apple tree we wassail thee

And hoping thou will bear.

It was recorded at Fordwich, Kent, in 1585, and appears in Devon in the 1630s, according to the poem by Robert Herrick:

Wassail the Trees, that they may bear

You many a plum, and many a pear...In the west of Britain the good health of the apple trees was toasted on Twelfth Night. The luck of next year's crop of cider apples was wished. Bread soaked in cider was put into the branches of trees to keep evil spirits away. Ritual songs were sung. It was reported thatcelebrants poured the remains of the cider kegs around trees in an orchard, dancing and singing the Wassailing song to ensure a good crop of apples for the following year.

It appears to feature again in the diary of a Sussex parson in 1670 and is quite frequently recorded thereafter. The fact that traces of it are found in fruit-growing areas of England under Elizabeth and the Stuarts argues for an origin at latest in the early Tudor or medieval periods. Modern guides to English folk-customs have frequently described it as a relic of pre-Christian ritual, and so indeed it may be. It may , nevertheless, also be an extension of the custom of the household wassail, made after the end of the Middle Ages.

In The Book of Days, Chambers describes a celebration on the eve of Epiphany, January 12: "In Herefordshire, at the approach of the evening, the farmers with their friends and servants meet together, and about six o’ clock walk out to a field where wheat is growing. In the highest part of the ground, twelve small fires, and one large one, are lighted up. The attendants, headed by the master of the family, pledge the company in old cider, which circulates freely on these occasions. A circle is formed round the large fire, when a general shout and hallooing takes place, which you hear answered from all the adjacent villages and fields. Sometimes fifty or sixty of these fires may be seen all at once. This being finished, the company return home, where the good housewife and her maids are preparing a good supper. A large cake is always provided, with a hole, in the middle. After supper, the company all attend the bailiff (or head of the oxen) to the wain-house, where the following particulars are observe: The master at the head of his friends, fills the cup (generally of strong ale), and stands opposite the first or finest of the oxen. He then pledges him in a curious toast: the company follow his example, with all the other oxen, and addressing each by his name. This being finished, the large cake is produced, and, with much ceremony, put on the horn of the first ox, through the hole above mentioned. The ox is then tickled, to make him toss his head: if he throw the cake behind, then it is the mistress’s prerequisite; if before (in what is termed the boosy), the bailiff himself claims the prize. The company then return to the house, the doors of which they find locked, nor will they be opened till some joyous songs are sung. On their gaining admittance, a scene of mirth, and jollity ensues, which lasts the greatest part of the night."—

The custom is called in Herefordshire Wassailing. The fires are designed to represent the Saviour and his apostles, and it was customary as to one of them, held as representing Juas Iscariot, to allow it go burn a while and then put it out and kick about the materials.Gentleman’s Magazine, February, 1791.

At Pauntley, in Gloucestershire, the custom has in view of the prevention of the smut in wheat "all the servants of every farmer assemble in one of the fields that has been sown with wheat. At the end of twelve lands, they make twelve fires in a row with straw: around one of which, made larger than the rest, they drink a cheerful glass of cider to their master’s health, and success to the future harvest; then returning home they feast on cakes made with carraways, soaked in cider which they claim as a reward for their past labour in sowing the grain"- Rudge’s Gloucester.

Here we come a-wassailing

Among the leaves so green,

Here we come a-wand’ring

So fair to be seen.

Love and joy come to you,

And to you your wassail, too,

And God bless you, and send you

A Happy New Year,

And God send you a Happy New Year.

We are not daily beggers

That beg from door to door,

But we are neighbors’ children

Whom you have seen before

Love and joy come to you,

And to you your wassail, too,

And God bless you, and send you

A Happy New Year,

And God send you a Happy New Year.

Good master and good mistress,

As you sit beside the fire,

Pray think of us poor children

Who wander in the mire.

Love and joy come to you,

And to you your wassail, too,

And God bless you, and send you

A Happy New Year,

And God send you a Happy New Year

We have a little purse

Made of ratching leather skin;

We want some of your small change

To line it well within.

Love and joy come to you,

And to you your wassail, too,

And God bless you, and send you

A Happy New Year,

And God send you a Happy New Year.

Bring us out a table

And spread it with a cloth;

Bring us out a cheese,

And of your Christmas loaf.

Love and joy come to you,

And to you your wassail, too,

And God bless you, and send you

A Happy New Year,

And God send you a Happy New Year.

God bless the master of this house,

Likewise the mistress too;

And all the little children

That round the table go.

Love and joy come to you,

And to you your wassail, too,

And God bless you, and send you

A Happy New Year,

And God send you a Happy New Year.

.jpg)

%20probably%20painted%20by%20Charles%20Bridges%20(1).jpg)